“You know Comunidad Inti Wara Yassi began in the city, working with young people, helping where there were no opportunities, no chances for education. Once, we went on a trip to the forest. We were all blown away by the trees, the animals. But we saw the forest burning, and we saw trees being cut down…”

Tania ‘Nena’ Baltazar is sitting on a low plastic chair, the hood of her fleece pulled up around her short, dark hair. Her cheeks are drawn, and her eyes are tired. It is 2019, and Nena has been working very hard for a very long time. We are in Parque Ambue Ari, a wildlife sanctuary on the edge of the Amazon. I have known Nena for over a decade, and this is the first time she has ever told me her story. It’s the story of how, over twenty-five years ago, when she was a student in La Paz, young and idealistic, in her first year studying biology, she met a spider monkey. That spider monkey would go on to change her life – and the lives of many, many others, including my own.

“Saben que Inti Wara Yassi empezó con ninos en El Alto, La Paz…” Nena smiles when she begins, decades of work, exhaustion, of fighting that have taken their toll on her body, and on her heart, melting away. Rain pounds on the tin roof and the smell of wet earth rises outside, heavy with the scent of mangoes. Through the rain, I can just hear howler monkeys calling.

“You know Comunidad Inti Wara Yassi began in the city, working with young people, helping where there were no opportunities, no chances for education. Once, we went on a trip to the forest. We were all blown away by the trees, the animals. But we saw the forest burning, and we saw trees being cut down…”

CIWY began as a project, started by Bolivian volunteers, helping children from poor families in Bolivia’s capital, La Paz. The children, once they saw Bolivia’s forests for the first time, and they saw the entangled ways it was being destroyed, created CIWY. With campaigns, marches and speeches, they – and Nena and the other volunteers along with them – became defenders of Bolivia’s ‘naturaleza’.

“We started doing more trips,” Nena tells me. “On one of these, we met a monkey. He was tied to the door of a bar, and people were feeding him alcohol and cigarettes. We thought the only solution was to free him. We climbed up into the jungle and let him go. But two days later, we were told he’d come back. And so we learnt – animals taken out of the jungle, cannot be put back so easily. After that…we started campaigning for wild animals directly. And me…I met another spider monkey. She lived as a pet in a family home, but the family didn’t want her, so I took her. She was called Nena.”

Nena laughs, shaking her head. In Bolivia, there were no sanctuaries for wild animals then.

“I took Nena to my house with the idea that I could improve her life. On the first day, she destroyed everything! My mama went so mad. She said if you want that monkey, you have to go. So I said, bueno. I got my backpack and left. Nena came with me. We spent three months moving around the houses of my friends. I didn’t know what would happen. I’d just started studying. Nena would roam free outside the university, and she would peer through the windows, watching me at my lessons. And when I’d take her baby carrier out of my bag, she’d know it was time to go. She understood things. And I started to understand things too. That Nena felt happy and sad, she felt pain, just like I did. We had a connection. Sometimes I’d go to the cobbled squares in La Paz, and there were so many people. Nena only had one metre by one metre of space, staying so close to me. And in those squares, there was one tree that was hers, just one, that she could climb… We didn’t have any money. We couldn’t find a place to stay. Eventually, I knew we couldn’t continue. With so much pain and hurt, I decided I had to give her to a zoo. There was no other choice. I took out her baby carrier. But for the first time, Nena wouldn’t come. She grabbed the bedpost and held on. Nena vamos, I pleaded. Vamos Nena. But she wouldn’t. She understood the decision I’d made. She saw it in my eyes, and I saw hers. Don’t leave me. Don’t abandon me.” Tears fill Nena’s eyes. “I said ok,” she continues, her voice breaking. “I promise. I won’t leave you. And she hugged me. She was so happy then.”

Nena then speaks about how she, Nena the monkey and a few of her friends, who had also rescued monkeys – five capuchins – left the city, following their dream to give their friends more than one square metre of space. They found a place called Machía, and it was there, in the cloud forests outside of Cochabamba, that they created Parque Machía, the first sanctuary for rescued wildlife in Bolivia. They had no money, no experience. Only passion, and a dream to give these animals a better life. Nena’s promise to Nena the monkey expanded, and soon she found she was making that same promise many times over. To a puma with broken legs. To birds, coatis, bears, jaguars and ocelots. They came with paws twisted, stomachs swollen, hearts and minds broken. Volunteers arrived, and CIWY grew.

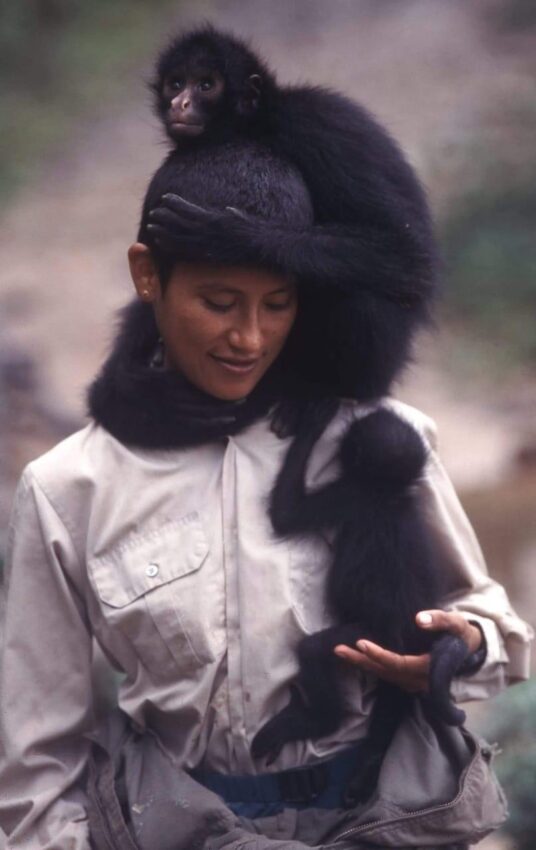

Photo Credit: Nena with her spider monkey kin, by David Gould

CIWY bought their own land, which they called Parque Ambue Ari, and a few years later another, the Land of Dreams, Parque Jacj Cuisi. They looked after children, remembering where and how CIWY had begun. Children who had no other place to go, with their own traumas. CIWY was able to send them to school and teach them about wildlife. Now most of them have grown up. They have become vets, nurses, construction coordinators…many still working and living in the sanctuaries. And volunteers have come from all over the world. Nena knows that most of these volunteers come thinking that they want to help the animals. But in reality, often it’s the other way around.

“Nena the monkey,” Nena smiles, wiping her eyes. “She was the monkey that changed my life. She lived for many years with us in Machía. She never became a mum herself, but she was the adoptive mama of many others, squirrel monkeys, spider monkeys…”

Nena stares out of the window. We sit together quietly, and the echoes of her words and her memories settle. Outside of this room, the jungle settles too. The rain has stopped, and there is just the slow drip of water from the leaves.

Twelve years ago, I came here and met a puma. She was three years old then, and I was twenty-four. Wayra: lost, confused and traumatised. Like so many other animals rescued by CIWY, as a baby she was cleaved from the wild places and brought onto the heavy colonised, capitalist, grey streets, where she became a pet. She suffered a deadly tragedy, a ripping of her identity. Now she is in her old age, almost fifteen.

CIWY has given her a life where, like Nena the monkey, she has more than one metre of space. She has a jungle enclosure that spans half an acre, where she can run, hide, feel the wind on her face, listen to the monkeys calling and smell the mangoes in the trees. She is loved, and loves back. She is lucky to be here and not in a zoo or chained up in a backyard. But it doesn’t matter. She is still lost. She is meant to be wild, and she cannot be. She didn’t ask for our care, or our love, and sometimes I sense it lies heavily on her. In a different world, wild animals like Wayra would not require such an intensity of human interactions, would not require feeding, being worried about, being near…but neither Nena, nor I, nor Wayra live in that other world. We live in this one and the desire for another doesn’t undermine the depth of love, silence and peace that CIWY offers. I said it doesn’t matter. But it does. Me, Nena, all of the other people who have visited and spent time with the animals at CIWY…we talk about them all the time. We think about them. We think with them. And as Donna Haraway says in her miraculous book Staying With the Trouble:

“It matters what matters we use to think other matters with; it matters what stories we tell to tell other stories with; it matters what knots knot knots, what thoughts think thoughts, what descriptions describe descriptions, what ties tie ties. It matters what stories make worlds, what worlds make stories.”

Wayra’s story matters. Nena’s story matters. Nena the human, Nena the monkey. And CIWY’s story, too. Because what CIWY does is to provide a world where beings who didn’t matter to many, matter more than anything. Animals, like Wayra, are cared for every single day. They are loved every day. Hundreds and thousands of people have spent time with them, walked with them in the jungle, swum with them, climbed trees with them, fed them, given them medication, touched their fur, talked with them… and those people have had their lives, and their stories, changed because of it.

That’s why I set up ONCA. At ONCA’s heart is also a space – an arts space, rather than a jungle space – made for thinking with. But as ONCA has thrived, far away in built up Brighton, CIWY’s frontline staff, their volunteers, and the wild animals under their care, have suffered – and so far survived – crisis upon crisis. But the crisis of this current moment is ripping CIWY’s foundations at the core. Covid-19 has affected Bolivia badly. An interim government, fragile in the wake of 2019’s violent riots and the subsequent exiling of socialist president Evo Morales, lacks the resources to fight this disease. Extreme lockdown is in place, prices have risen, and communities are confused, isolated and fearful. Crisis is not new. There has long been instability and corruption in Bolivian politics, colonised many centuries ago, and made up of at least 36 different Indigenous cultures. Now, economic development is an unstoppable force, even in a country that refused McDonald’s. Forest fires escalate year on year, heavy with the scent of smoke and death. Climate change accelerates. Bolivia’s jungles disappear as cattle farms and logging projects continue apace, combined with the onslaught of the illegal wildlife trade.

Nena has seen it all. This year, with the threat of a road expansion hanging over her head, set to devastate the jungle on which Parque Machía depends, the local government have decided they want their land back. Nena, all of Machía’s hundreds of animals, and the people who have made the sanctuary their home, will have to leave. They hope to relocate to Jacj Cuisi, but the future is unstable. CIWY makes 80% of its income from international volunteers, whilst also depending on those volunteers to help care for the animals day-to-day. This is a failing model, but it has helped them survive until now. But these last months, CIWY’s income – approximately $22,000 per month – has gone down to zero, and support within the sanctuaries reduced to bare bones. There are no volunteers. This must be seen within its context – set against the destabilisation of the Amazon fires in 2019, the recent political unrest, and the new threat of even more devastating fires this year. CIWY’s financial reserves will run out by August. Nena and her staff are now facing the very real possibility of closure as their ‘normal’ in crisis meets the ‘new normal’ of a global pandemic. Covid-19 was likely brought about in part by deforestation and the pressure of humanity on wild habitats in Asia. A snapshot of the effects this disease has had – both directly and indirectly – on Nena’s community gives a view into the interconnectedness of global crises, the resilience and entwined vulnerability of frontline indigenous, Black and POC communities, and the resilience and entwined vulnerability of biodiversity. Covid-19 has forced, and is forcing, many people who have lived through crises for decades, and inherited crises over centuries, to consider yet again what may be the breaking points, and how it may be possible to identify them when/if they arrive.

How to stand in solidarity then? Lilla Watson, Indigenous Australian and Murri visual artist, activist and academic, famously said:

“If you have come here to help me you are wasting your time, but if you have come because your liberation is bound up with mine, then let us work together.”

I speak to Nena whenever she has the time – not together now, but across an ocean, connected just barely through a WhatsApp call – and each day she sounds more tired and more uncertain. The rains still pound down on the roof without stopping, until, of course, they will stop and then the smoke from the slash and burn fires will return. Nena will still be there, as will all the other allies and staff who have given their lives to those places, and those beings. Whilst across the world, hundreds of thousands of others – although unable to be there in person – will continue to witness, and think with, and stand by their side. Entangled in countless liberations. Searching for practical acts of solidarity. Writing blogs. Reading, learning, expanding. Ceding voice to, and sharing, vital stories. Donating money to frontline Indigenous, Black and POC-led projects. And above all, returning again and again, as those of us who are safe, warm and comfortable must, to those that have been stepped over, are being stepped over, and are under threat every day from systemic violence.

Support CIWY

To provide vital support for CIWY, the people, the wildlife and their jungle communities, please sponsor one of CIWY’s animals or make a donation at www.intiwarayassi.org.

—

Share on Twitter /

Share on Facebook

Posted on July 15, 2020

Categories: Endangered & Lost Species, Environmental Justice & Activism

Tags: Comunidad Inti Wara Yassi, Laura Coleman

→ My ONCA Story by Ella Husbands

← My ONCA Story by Lily Rigby