Lino Waves: Soundscapes of The Living Coast was an exhibition by sound artist Daisy Stewart-Darling in collaboration with Sussex Digital Humanities Lab, The Living Coast and Fabrica. The exhibition showcased a culmination of work researched and developed as part of The Living Coast Artist Residency 2024. Below, Daisy-Stewart Darling delves into the finished artworks, research and processes as this years selected artist.

Elm, 2024

Image by Gurnoor Singh

Carved black-stained linoleum, with gold foil touch points.

In the UK, we only have around 60 native species of trees, with the Elm as one of our most ancient cohabitants.

The Preston Twins, located in Preston Park, are thought to be the largest and oldest surviving elm trees in Europe. Tragically, the one featured died from Dutch Elm Disease in 2019. Thanks to artist Elpida Hadzi-Vasileva, it’s been preserved in its newly gilded form as a memorial to the trees that were lost to the disease en masse since the mid-20th century. I was really moved by this.

More recent biological research on tree and plant behaviour challenges existing understandings of their intelligence, and recognises these beings as intelligent in their own right. For example, we now know trees communicate to one another through mycorrhizal networks, with elder trees sending nutrients to younger trees in need, and able to detect sickness in nearby trees. This has started to raise ethical conversations surrounding trees as sentient beings. This was at the forefront of my mind when considering how trees might experience their sonic environments in contrast to my own when field recording around The Living Coast.

Consequently, I decided to dedicate this piece to the Preston Twins’ experience of the biosphere with a view of subverting our human-centred listening experience and instead considering other organisms’ perspectives of these shared spaces.

Field recordings from around the park are interlaced with vibrations from the living elm itself to imagine how it might experience its sonic environment. I also include contact mic recordings of the railings separating the dead elm from the rest of the park, which resulted in a surreal version of the same sound environment.

The Living Coast: Contour Map

Image by Gurnoor Singh

Carved black-stained linoleum, with gold foil touch points.

Over the duration of the residency, I travelled across The Living Coast, collecting a vast volume of field recordings from the locations marked on the map.

Along the way, I met lots of residents and had many interesting conversations about areas of the biosphere that are important to them which then informed the specific locations to capture and compose soundscapes.

It was a privilege to hear their experiences and concerns regarding changes in sound pollution affecting the areas they cared about. In some cases, I was able to support people to hear the environments they’d been inhabiting all their lives in a new way. For example, by showing them underwater soundscapes in ponds or contact microphone recordings of trees they know well.

The result was this map of sonic sites. I find it so interesting having them all within one piece, allowing us to hear the contrast of different locations that make each unique.

I chose to display this as a contour map, as it made sense to emulate the natural carving of the landscape through centuries of natural weathering and shaping by recutting it myself in the lino. It felt good to physically follow the flow of the land’s layout within the cutting process and for this to then become the interface for people to interact with recordings of the environments keyed on the map.

Chalk Reef, 2024

Image by Gurnoor Singh

Carved linoleum painted with foraged, handmade chalk paint from the undercliff at Ovingdean. Finished with gold foil touch points.

I chose the chalk reef as a main subject, as it is currently one of the only protected marine conservation sites in the Southeast of the UK, and upon exploring it I found it both visually and sonically really surprising.

At low tide the reef is exposed, revealing an alien-like landscape. The shapes are formed from centuries of the chalk being ‘cut’ by a tide of waves, which led me to want to recreate cutting this into lino.

I arrived at the reef expecting to capture a big seascape set of recordings, but instead was struck by so many tiny, intricate sounds hidden within the reef itself. The more time I spent listening, the more I was drawn to the bed of crackling seaweed that at first I’d overlooked. After a few hours of exploring, rock pooling and discovering all the colourful anemones, shrimps, crabs, and fish. I started picking up all these ‘hidden’ sounds with contact and hydrophones of underwater photosynthesising plants, bubbling sea snails and barnacles crunching rocks.

The result is a set of recordings from different layers of the beach from the cliffs right down to the reef bed itself. It challenged me to listen more closely to what was actually going on in these environments, and compose soundscapes led by the reef, not by what I expected from a coastal space.

Decentralising my expectations as a human listener and paying attention to the subtle sounds of what was happening when I slowed down and immersed myself was very humbling. It turns out there is a very vibrant world of sound we don’t normally have access to but that exists and is the norm for other organisms’ daily experience of the biosphere.

The paint used on this lino was made from fallen pieces of chalk from the cliffs.. Chalk itself is a white limestone formed from the remains of tiny marine organisms from 70-100 million years ago. From the plants used to make the lino, paint from the chalk cliffs, to the intricate layers of sounds from the biodiversity living within the reef, every element of this piece was made possible from the materiality of the land. I hope it helps people to reconnect and experience The Living Coast in a different way.

In The Field

Seven part, black and white photo series on A3 paper.

As I passed through areas on my field recording adventures I took snapshots of locations.

Linseed

Image by Gurnoor Singh

Dried linseed plant.

Linseed or Linum usitatissimum, as is its scientific name, is the oldest cultivated plant dating all the way back to the upper Palaeolithic period 30,000 years ago. It is the same plant Ancient Egyptians used to make linen to embalm and wrap mummies with, and that Romans used for sails in their ships. We tend to use it still in fabrics but also in lots of wood finishing products in construction. It’s more familiar name is flaxseed, which is a common ingredient in vegan substitutes such as non-egg ‘eggs’.

I’ve been thinking a lot recently about how essential plants are in everyday products. From food to clothes, they are a key ingredient in countless materials and medicines. I’ve been challenged on how much and often I take plant technologies for granted. Learning more about linseed – a key component in the lino I use – has been an honour and I’m grateful to creatively collaborate with this plant that’s been a partner to thousands of generations of humans. Especially, to create a body of work seeking to elevate non-human voices in conversations surrounding conservation.

It felt important to highlight and make space to consider just one of the many plants are involved in the materiality of this work, without which, it wouldn’t exist as it does.

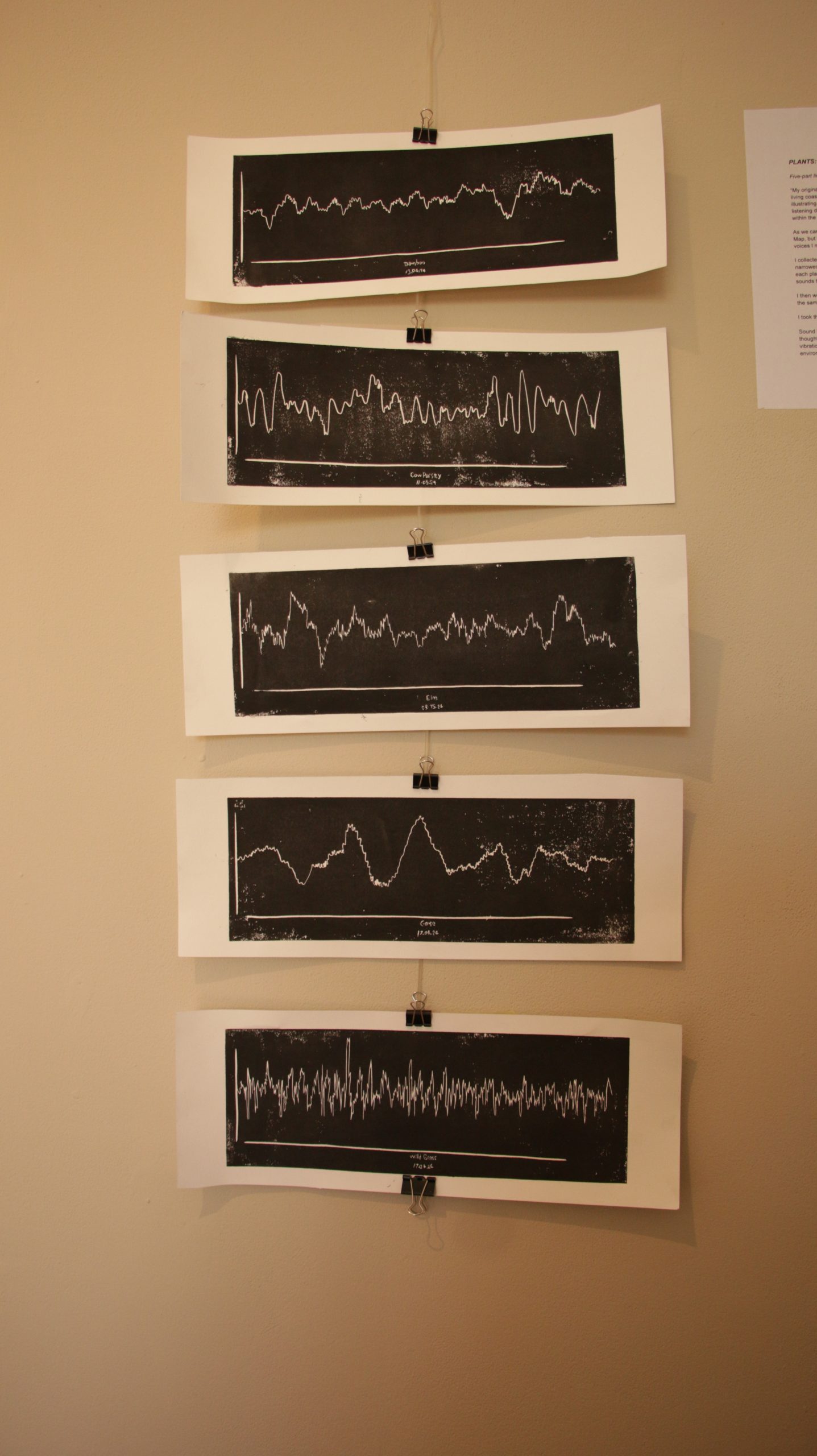

Plants: In Sound Waves, 2024

Image by Gurnoor Singh

Five-part lino print series in black ink, on Fabriano Paper.

My original proposal focused on presenting different environments within The Living Coast as various sonic visualisations. This was with a view of illustrating different ways we perceive sound, as part of a wider theme of listening differently, and connecting through listening to other organisms within the biosphere.

As we can see today, I developed this concept into three large interactive artworks: Elm, Chalk Reef and the Contour Map. However I wanted to platform some of the plant voices I met during my travels so I collected contact mic samples of various plants when field recording and selected a few. I found it interesting how tonally different each plant sounded on closer listening, and the different percussion sounds they produced.

I then worked with coder Rachel Locke, who wrote a code to translate the samples into different sonic visualisations. Afterwards, taking this data and I designed, cut and printed them as lino prints.

Sound is the vibration of molecules that travels in acoustic waves. I thought it was interesting to see the differences in behaviour of vibrations of different plants/trees and how they’re interacting with their environments, and how they might experience sounds on a daily basis.

Process

Stages of producing the work.

Besides physically going out and making field recordings, then composing soundscapes, designing and testing each piece of work took considerable amounts of time.

Each stage came with its own set of challenges, from developing the concepts, to figuring out how to design and transfer these onto five-foot pieces of lino. This was then followed by prototyping the link to check it would work technically to produce an interactive soundscape.

These are just some of the processes behind the results you see displayed here.

—

Share on Twitter /

Share on Facebook

Posted on June 20, 2024

Categories: Artists in Residence

Tags: Daisy Stewart-Darling, Fabrica, Lino Waves: Soundscapes of The Living Coast, Sussex Humanities Lab, The Living Coast