Helen Cann is an established illustrator and artist. She has been published in over 30 books, illustrating tales, stories and poems. In her illustration work Helen pays particular attention to the world and its creatures: “I love painting and drawing animals, birds and plants; I look for patterns in everything and find so much beauty in the natural world.”

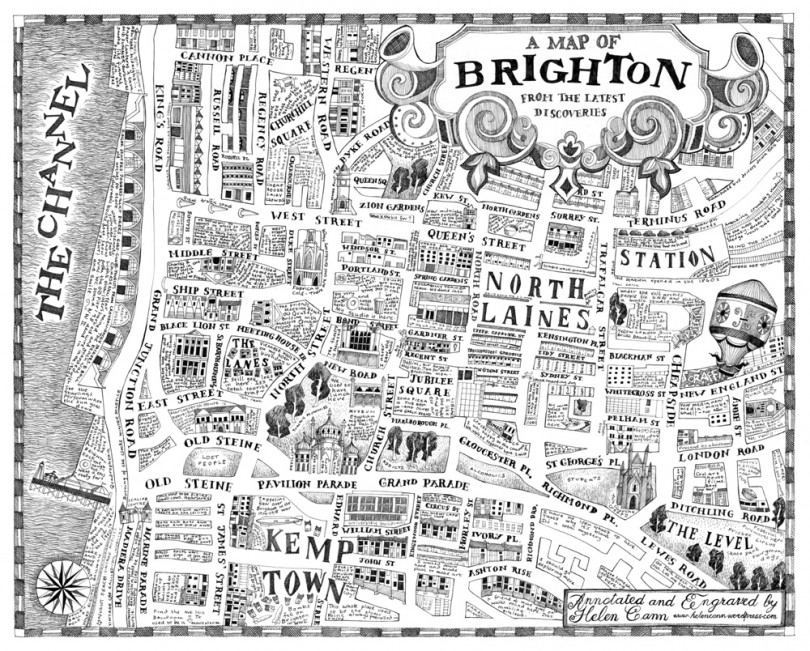

In the past few years her fine art practice, emerging through gallery exhibitions and supported by the ONCA Gallery, has concentrated on hand drawn artists’ maps.

Helen Cann A map of Brighton from the Latest Discoveries

Helen Cann A map of Brighton from the Latest Discoveries

As a visual artist, Helen thinks about the way we read images and how we gain knowledge by sharing signs. She explains: “From childhood, we learn about life by decoding symbols. Somehow we are supposed to use the decoding to make sense of the world, using our knowledge, experience and education.”

Helen developed an interest in traditional maps, even more so since Google Maps and GPS have become the go-to source for navigation. She is fascinated by the mystery, stories and character of maps transcribed on paper, however she wonders whether we are losing those elements.

In her latest hand drawn projects, Helen has been working with maps and words, in particular she is interested in the relationship between the way words look and how they change the viewer’s understanding of an image, how they can suggest a narrative, a time or a place: “I use words in my paintings to do exactly that but of course, they can only act as a suggestion to meaning. Decoding always depends on the decoder.” As an artist, she also uses words as tools and graphic signs in order to fill her hand drawn maps with stories and details about places: historic, contemporary, anecdotal, personal, fictional and real. She maps the subjects and places that interest her, giving the urban as much importance as the wilderness.

Even well known territory can throw up new discoveries when you open a map. The names of every river, every holt and coombe narrate a tale of human interaction with them. In order to value our environment and make efforts to protect it, Helen’s work is a way of showing that we need to positively accept our place in it. We are of nature, not outside nature. We are part of and have been part of the environment for centuries and our traditional maps show this. By recognising the value of individual human narratives within the environment, she suggests that we might cherish those places just a little bit more.

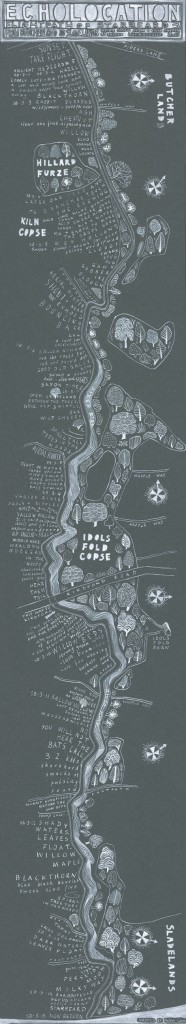

Another project, ‘Echolocation’, commissioned by ONCA and in collaboration with Sussex Wildlife Trust, maps the flight path, probably centuries old, of a rare Barbastelle bat. Alongside the contemporary scientific data provided by Sussex Wildlife Trust, the map also describes the local history and folklore of that part of the Weald and some of the 30 different words for mud in the Sussex dialect. For Helen, the sounds of both man and bat echo in the area help figure this particular environment, and perhaps allow us to value the landscape better, and therefore the Barbastelle habitat, itself. This long map shows a cross over of nature and culture, by displaying the bat path alongside the human language, both in relation to a specific land.

Helen Cann Echolocation

In the summer of 2014, four artists, among those Helen, became part of the crew of Sea Dragon, a steel sailing boat that journeyed 1300 miles across the Atlantic Ocean from Reykjavik in Iceland to Gothenberg in Sweden. Working with marine biologists, scientists, documentary filmmakers and an Icelandic sea captain, they spent their time on board searching the waters for whales and dolphins. As part of Whalefest 2015, the world’s largest festival about whales, dolphins and marine life, they held an exhibition at the ONCA Gallery, their final destination point.

During their journey, the artists helped crew the boat but also mapped whale sightings onto an international marine conservation database.

Laura Coleman, founder and co-director of ONCA, also sailing with the crew wrote a weekly blog on their time on the boat:

“For others, like illustrator and fine artist Helen Cann, the extra time is enabling her to top up her collection of local knowledge. She is putting together data to make an artist’s map, describing how people use more than physical geography to locate themselves. Story, dialect, history, economy, science and culture all feature on her maps, as she is interested in how people understand their place – both physical and emotional – in the world.”

Indeed, the piece became a chart of the voyage covered with travellers’ tales, both contemporary and historical, interspersed with fantastic stories of whales and whaling from the past. She collected stories from the crew. She collected stories about whales from Grindadrap hunters in the Faeroe Islands, from tour guides, harbour masters and bartenders… However it wasn’t an easy task, because of the lack of people willing to open up about how cetaceans feature in Icelandic culture.

Helen understood that the stories men tell about the oceans had changed very little throughout time. The stories of pirates, ghost ships, mermaids and rum were still being told alongside the stories of fabulous sea monsters, that were often chased, half glimpsed but never fully seen. The cultural value of whales shouted out loud and strong as did the cultural value of the sea. Every story had a connection with a particular place and often the naming of those places reflected that. With GPS technology we lose sense of these stories and our historical relationship with the waters.

Traditional cartography is becoming a lost art with the ubiquity of soulless GPS and Google Maps. All those stories that truly allow us to understand a place, once illustrated on maps, will be abandoned and perhaps we should be more aware of what we are losing. Gone will be those marks we have made on the landscape, the naming of villages, the fighting of battles, the dew ponds and drove roads and echoes of settlements. All these will be lost stories. And by losing them, we will have one less reason to appreciate and protect our environment.

For Helen, it’s important to express that there is more to a place than simple geography and that there are multiple ways to understand, describe and navigate our world other than the digital. Traditional maps tell stories and we should be careful not to forget them.

You can see more of Helen’s work on her website here.

Find out more about The Whale Road project here.

—

Share on Twitter /

Share on Facebook

Posted on April 11, 2016

Categories: Artist Development

→ Artists in Residence: Space, City, Land, Sea

← Review: Earth at ONCA