For our autumn blog series, eminent US-based artists Alexis Rockman and Mark Dion share Two Artists in the Age of Pessimism – a conversation from 2013 about the role of the artist.

Alexis Rockman: Mark, I want to talk about our outlook on art and how it may have changed in terms of things that we care about in our work and in our lives. Do you feel more or less hopeful about ecology, conservation and biodiversity than you did when we both started our careers in the mid 1980s?

Mark Dion: I fear the trajectories of our thoughts about wild lands and wildlife conservation have been parallel. It is a long train of ideas that terminates in pessimism and melancholy. If I had to categorize my thoughts and feelings about ecology over my development as an artist, it would form a list like this:

– Amazement/Wonder

– Curiosity

– Outrage/Anger

– Hope/Activism

– Disillusionment

– Pessimism/Melancholy

We were both fascinated by a wonder and love for animals and wild places. This became the motivation for reading about natural history and zoology in particular, which led to our understanding of the challenges of wildlife conservation issues. At one point I became convinced that environmental issues were really information problems. I believed that if people knew the damage their way of life caused to the natural world, they would change. I believed that people would opt for environmental sanity over ecological suicide. My early work tended to be quite informational and didactic since I was literally attempting a kind of sculptural documentary practice.

After a while it became apparent that access to knowledge wasn’t the problem. Ecological knowledge was readily available. The main issues were questions of political will, ideology, capitalism and psychology. It is hard to say that people don’t know about the crisis in biodiversity because the information is everywhere.

For me it is clear that we will continue our disregard for other living things and the degradation of the environment to suicidal extremes. This leads me to a perspective of pessimism. However, I would love to be proven wrong. Dark conclusions and complex positions that end in ambivalence are difficult to articulate in various forms of culture. You cannot express these sentiments in politics, in activism, perhaps even in journalism. Art is an excellent place to express complexity, paradox, uncertainty, ambivalence and hopelessness. The role of the artist as witness can be as valuable as the artist as catalyst.

Don’t you find a great deal of pushback from the environmental community you sometime work with when it comes to issues of pessimism and doubt?

Alexis Rockman: Yes, there is a lot of pushback from the scientific and environmental activist community. They might confess privately that they are despairing, but they often feel that if they articulate this in public, people will flee as if from a burning building. Well, it is a building on fire, and it’s terrifying. I’m grateful to have art as a way to cope. One of my jobs as an artist is to show how we can’t afford to be ambivalent about human activity.

Obviously, it’s easy to be confused by what fuels our behaviour and motivation. Knowledge just isn’t enough. Our behaviour has as much to do with the Pleistocene as it does with the 21st century. What I mean is we are tribal, territorial animals who are afraid of mortality. We really can’t imagine what the world will be like two years from now, let alone one hundred years. This is an unfortunate cocktail of paradoxes for everything else alive on this planet. I often try to imagine what the person who cut down the last tree on Easter Island was thinking about in 1600 BCE.

Like you, I used to believe that knowledge and information would open our eyes to the environmental issues and create radical change in behaviour and save the world. I made art to teach a lesson. But I learned the lesson from Al Gore’s An Inconvenient Truth that people, if they will listen, just don’t have the collective will to do much. The engine of capitalism is just too powerful.

AR, Bronx Zoo, 2013, oil on wood, 84 x 168 inches

How do you think future generations will perceive this period in history, now that our impact on the planet is an undeniable and acknowledged fact?

Mark Dion: I guess we could look at how we feel about those who made selfish, corrupt and unforgivable choices in the past. How do we feel about those who clear cut the entirety of New England? How do we feel about the agriculturalists who killed the last Carolina Parakeet, or the market hunters who raided the last passenger pigeon nest site? How to we feel about those who administrated the trail of tears and other schemes of genocide? How do we judge those who brought buffalo and wolves to the very border of extinction? How do we judge the chemical magnates who attacked Rachel Carson, employing the notion that a woman could not produce good science?

If it is true that we are the last generation that can significantly change the course of environmental degradation and we end up doing little or nothing, then I imagine our place in history, as the enablers of shaping the planet as a crummier place, will not be terribly noble.

I am not sitting on the moral high ground and wagging my finger. I am very much implicated in the problem. I am far from a paragon of environmental sainthood. While we need some leadership and models of a positive culture of nature, it seems to me very much a question of values under capitalism.

Where does art fit into this?

Alexis Rockman: Art is one of the few places where one can have a singular voice that challenges corporate globalism. However, there can be surprises too. It is possible to find oneself in bizarre professional paradoxes. Over the years art and arts organisations that we love have taken financial support from companies or sponsors that would be at direct odds with our conscience and political positions of our work. People like the Koch brothers are very involved in philanthropic activities around the country. The American Museum of Natural History will enjoy a new Dinosaur Wing thanks to David Koch’s $20 million dollar donation. They even had their name on the building where I just had surgery.

What does one do when the potential benefactor is at least a symbol of the very problem?

Mark Dion: To paraphrase Vladimir Ilyich Lenin: the capitalist will sell us the rope with which to hang them. Of course, Lenin never had to deal with the sophisticated greenwashing tactics of multinational corporations—paper companies that portray themselves as defenders of the forest, or oil corporations who sell an image of pioneering alternative energy campaigns.

We live in a world of contradictions and compromises and artists are certainly not immune to the everyday-life conflicts of anyone living under capitalism. It is hard to participate in the global art world and not have a significant carbon footprint, for example. Some of the staunchest environmentalists I know board a lot of jets.

I guess one has to assess actions on a case-by-case basis. Every opportunity provides fresh challenges and opportunities, but they are each also a gamble, meaning sometimes you win and sometimes you lose. In general, I think environmental groups overestimate the importance of individual contributions to problems, making it seem like one’s choice of light bulbs or household recycling are real solutions. This tends to let the policy wonks, elected leaders, corporations and other masters of the culture of consumption off the hook.

As long as your sponsor does not control your content and you have no intention of changing your work, I say take the money. I don’t really know of any clean money in the world. You must be careful and cautions of how you are being used, and be certain that your content cannot be co-opted to contradict your convictions. No greenwashing.

You depict a good deal of trash in your work. What does it mean to you? How does it function in your iconography?

Alexis Rockman: Trash. It works for me in a number of exciting ways. When I first started to paint natural history landscape paintings in the 1980s, trash was a big thrill. It was something that hadn’t really been included in the history of painting and seemed like a taboo. There was something perverse about painting it in a loving and careful way. Trash was also a way to stake out my own territory. I was aware that one can’t make a painting about ecology in the 20th or 21st century and not include it. It’s everywhere, whether visible on a beach or on a microscopic level, and it’s the reality of the state of the planet. One of my earliest memories was being in Lima, Peru and seeing what looked like mountains of trash clogging the river. To add insult to injury, it seemed as if the trash was covered in vultures. It terrified me particularly because at home I lived near the East River in New York City and I was afraid that might happen there too.

You have travelled to as many “dream” destinations as anyone I know. Is there a place you have yet to go that is at the top of your list?

Mark Dion: I have been to some remarkable places—both remote and natural, and highly populated and cultured—but what makes traveling fulfilling is the company I’ve shared. Travelling with people who share my passion for wild places and commitment to conservation but who came with such different sensibilities and strategies was amazing.

Artists and scientists are obvious allies when it comes to environmental justice and wildlife issues, but they speak different languages and employ entirely separate toolboxes in their approach. The GYRE expedition to the trash-strewn beaches of Alaska was a real model of the kind of travel I would like to do more of. The team was relaxed, yet highly committed and remarkably intelligent and thoughtful. I had not imagined that the expedition would be so productive and that we would all get along so well, but of course it makes sense given we all share them same concerns. Needless to say, there is always a sense of urgency in nature travel today since so many wild places are under pressure. It is easy to get caught up in “the last chance to see” mentality. Places you and I travelled to in the 1990s have become drastically degraded. Many of the forests you visited in Madagascar are gone forever. For me, the importance of travel is that it affirms my connection with wild places and makes me give a damn. It is easy to lose a sense of what we’re fighting for, so I find visiting wild places essential to keeping my focus. The idea I mentioned earlier about the artist as a witness is also an important dimension of conservation travel. Artists were important to the process of documenting new animals as they were first identified to science. Now they are equally important in documenting their disappearance.

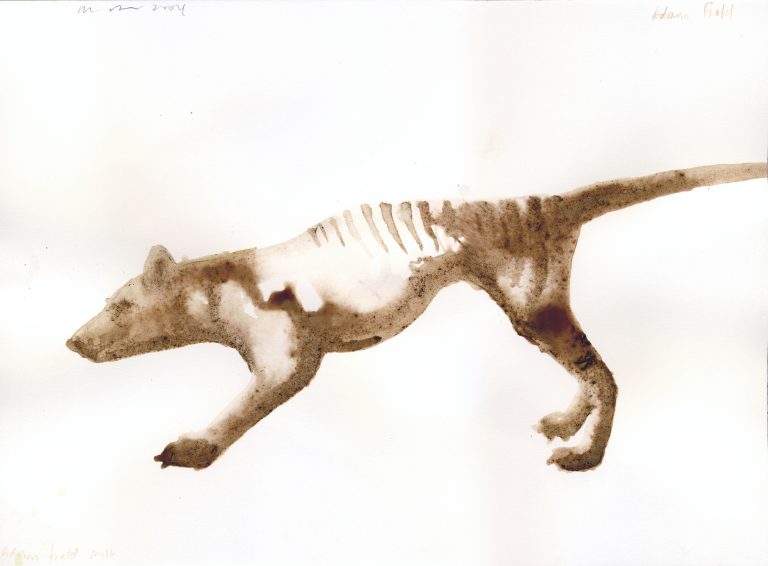

AR, Thylacine, 2004, soil from Adam’s Field, Tasmania and acrylic polymer on paper, 9 x 12 inches

—

Share on Twitter /

Share on Facebook

Posted on October 3, 2016

Categories: Interviews

Tags: Alexis Rockman, Mark Dion

→ Harvest Hack with MakerClub

← The Animal Nature and the Psyche – The Art of Jan Harrison